Preserving Dunbar: The Culture and Legacy

The first graduating class voted to rename the school Dunbar High.

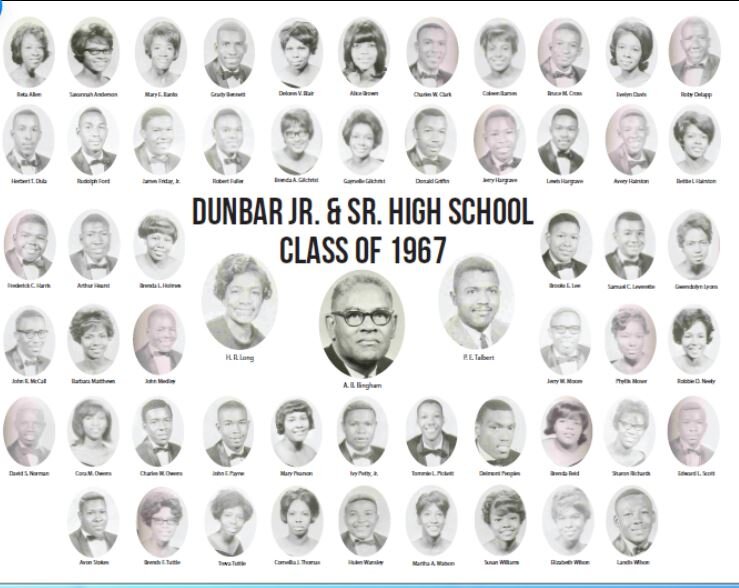

{Contributed photo/David Norman}

*This is the last article in the Preserving Dunbar series.

In Lexington, the name Dunbar is synonymous with history, pride, community, education, dedication and winning. Before integration in 1968, Black students were educated at schools bearing the name Dunbar.

What started out as a place of learning in the 1920s developed into a culture that remains richly intertwined within Davidson County.

The Rosenwald Schools

Early in the 1910s, Booker T. Washington, educator, activist and founder of Tuskegee University, had an idea. Recognizing Black children needed schools, the former slave began highlighting the knowledge, expertise and proficiency of students in hopes of convincing power players in the deep South of this fact.

With his effort falling on mainly deaf ears, he consulted his friend, Julius Rosenwald, a member of Tuskegee’s board of directors. At the time, Rosenwald was the president of Sears, Roebuck & Co. Washington expressed his desire to see schools constructed for Black children and asked Rosenwald if he would finance them.

Willing to test the waters, Rosenwald initially funded six schools in Alabama. Witnessing the success of the project, the philanthropist created a fund to assist in the construction of schools across the South. By 1932, with the help of matching grants and donations raised by citizens, mostly Black in the communities where the institutions were being erected, over 8,300 schools had been built.

Dunbar 4th St. School

During the early 1920s, Black students attended the Colored Graded School on 4th St. According to information from Fisk University, during the 1926-27 budget year, the school received $52,100 to construct new buildings and add teachers.

The database lists the funding sources as: Negroes - $1,000; Public - $49,000; Rosenwald - $2,100.

Students pose outside of Dunbar 4th St. in an undated photo.

{Contributed photo/Davidson County Historical Museum}

Also, during this time, students voted to change the name to Dunbar High School. The name was selected as a nod to the contributions of Paul Laurence Dunbar who is widely viewed as one of the most influential Black poets in American literature. The mascot was the Blue Devils.

Over the years, many who attended and graduated from the school eagerly shared their memories. Rooted in many of the conversations is the presence of unity and support as well as the atmosphere that groomed students for success.

Louise Miller and Dollie Reid, 1950 and ‘51 graduates, respectively, of Dunbar High School (on 4th St.) recollected aspects of their lives as a students. From community encouragement to memorable moments with friends, Miller recalled those years with a smile.

“Every day was a fun day,” Miller remembered. “Students had recreation without technology or expensive toys and games. On May Day, the students wrapped the May Pole and had competitive events. It was a big celebration. The community was supportive of the school, involved in all activities and spent many volunteer hours making it a success.”

Every year, thanks to community support, the school produced an Operetta. The Glee Club was renowned and sent members to state competition yearly. On the athletic front, football was the premier sport since the school didn’t have a gymnasium. Throughout the years, the team made the playoffs on many occasions and won state championships.

Students in the library at Dunbar 4th St.

{Contributed photo/Dunbar Preservation Society}

Even though many of their books were “deemed obsolete by the White schools,” teachers didn’t limit their expectations of students. Nor did they limit their own expectations as many of them traveled to New York to earn advanced degrees.

“The teachers were supportive in the classroom and outside,” said Reid. “They pushed and prepared the students to become productive citizens, academically competitive and successful. Many professionals were products of Dunbar 4th St. If something happened at school or you were not performing to your best abilities, the teachers visited your home, and your parents were very receptive and supportive.”

Additionally, Miller and Reid noted one of the advantages to attending school on 4th St. was the fact the grades ranged from first to twelfth. Given the nature of the times, during lunch those who lived close by were able to go home while others brought food with them. A cafeteria was built in later years.

As the years continued, Black students thrived under the leadership at the school. After graduating from Dunbar, many alums embarked on various paths including secondary education, the military and entrepreneurship.

This way of life extended to the Southside of Lexington when the new Dunbar Junior-Senior High School (DJSHS) was built in 1951. The 84,617 sq. ft. building opened in 1952.

Smith Ave.

With the opening of DJSHS, grades seventh through twelfth were housed on Smith Ave. Students in grades first through sixth continued to attend Dunbar 4th St.

Dunbar High School on Smith Ave,

{Contributed photo/Charles Owens}

Rev. Dr. Arnetta Beverly, pastor of St. Stephen United Methodist Church, attended school at both locations. As she evoked that period, one of the first memories that charges to the forefront of her mind is the opening line to the alma mater, “Hail to thee, dear Dunbar High…”

Although she enjoyed her time at 4th St., Beverly said she was eager to go to seventh grade because she wanted to attend the new school despite not being allowed to mingle with the older students. Plus, her love for comprehension and imagination received a boost.

“When I got to the high school, seventh and eighth graders weren’t really allowed ‘up the hall.’ That was for the high school students. The library under Mrs. Lucille Bingham was the most wonderful place. I could go all over the world and be whatever I wanted to be through reading books.”

At DJSHS, alums have noted that the same sense of pride that was instilled in them at the 4th St. school carried over to Smith Ave. Even with two locations, the Dunbar family remained unified at its core. The expectations from faculty and staff didn’t change just because the institution where they received their education did.

{Contributed photo/Dunbar Preservation Society}

Another trait that remained intact was the prowess of the athletic programs. Coach William “Sugarlump” Bryant guided the Blue Devils to two football championships. In 1957, he was replaced by Charles England, who passed in 1999. England also served as athletic director. Under his tutelage, the school won the state championship in 1963. England, a North Carolina High School Athletic Association Hall of Fame inductee, is credited by many with being a catalyst for change and positive influence for young men during those times. He was also inducted into the Lexington Senior High School (LSHS) and Davidson County Athletic Hall of Fames. England’s inspirational phrase, “Be Somebody,” serves as the motto for Lexington City Schools.

In recognition of their accomplishments there have been additional Dunbar graduates who have been inducted into the LSHS Hall of Fame. They include Libby Matthews Johnson, Roy Holt, John Medley, Produs “Scott” Perkins, William Marshall Dusenberry, William “Buddy Walser, Jimmie Bryson.and Larry “ToJo” Burns.

Along with their stout football program, the school was widely known for its marching band. Ned Fowler, the president of Shelter Investments Development Corporation, which is planning to repurpose the Smith Ave. building into affordable, senior apartments, grew up in Winston-Salem and was afforded many opportunities to see the band in person. “I remember seeing them perform when I was a kid. Their band was the best around.”

Beverly, a 1964 graduate, agreed.

“I was a majorette and we had the best band in the land. For our football homecoming, the band would gather at the school on E. 4th St. We would march up 4th, turn left onto Pugh St., then right onto 3rd St. and finally hit Main Street! When we got to the Square, we really turned it on and turned it out! Then we would rest at houses in Lincoln Park until game time. The Dunbar Blue Devils usually won the game and championship.”

While viewpoints began shifting throughout the country regarding the Supreme Court’s decision that segregation was unlawful, Dunbar and its students continued to flourish. As Black students commenced testing the waters by attending the all-White Lexington City Schools system, Dunbar remained a cornerstone in the community.

However, the directive from the highest court in the land inevitably sealed the fate of Dunbar as the primary educational institution for Black students. Having still been in operation for years due to the unhurriedly process of desegregation, a decision was made in the late 1960s to integrate. The Dunbar High School Class of 1967 was the last graduating class.

Dunbar remained closed for a year before reopening in 1968 to service sixth- and seventh-grade students. Later, it transitioned into an intermediate school that housed fourth and fifth graders. The school closed in 2008 when (then) Charles England Intermediate School relocated to Cornelia St.

The Legacy

There is no current information available as to when the majority of the buildings on 4th St. were razed. The school’s cafeteria was still erect until a few years ago. It was heavily damaged in a fire. Much to the ire of many in the community, the city of Lexington, who owned the building, made the decision to demolish the remains.

To preserve the memory of both schools, the culture and the legacy, Dunbar alums and attendees began holding reunions yearly. What started decades ago as a chance to gather to reminisce and share stories has grown into an extended family connected by a shared experience.

At the turn of the century, Charles Owens and the late Rev. Dr. Ronald Shoaf spearheaded an initiative to secure funding to purchase the building on Smith Ave before a decision was made to vacate it. Although unsuccessful in their attempt, they diligently worked for a year to have the building included on the North Carolina Office of Cultural Resources study list. It was added in 2008. As a result, the building cannot be torn down or altered.

Owens has continued to conduct research on the history of the Dunbars. He is the creator of a Facebook page, Dunbar Preservation Society, where he shares many historical facts and photos.

Despite the 4th St. school being destroyed and the proposed plan of the Smith Ave. building, Beverly believes the Dunbar legacy will live on forever in the hearts of those who experienced all it had to offer firsthand.

“Whether on 4th St. or Smith Ave., Dunbar School will always be remembered by the alumnus – The Dunbar Blue Devils.”

*All historical data is based on information available.*